Do you live in a period house? Perhaps it’s Edwardian era, Victorian or Georgian? If you do, you’ll likely have come across lath and plaster construction. But what is this building method? Why is it no longer in widespread use? And should we worry about preserving it as a heritage feature? Or is it simply out with the old and in with the new?

What is lath and plaster?

The lath and plaster technique was generally used to finish interior walls and ceilings from the 1700s to the early-to-mid 1900s before it was superseded by modern gypsum plaster and plasterboard.

Lime plaster was traditionally used to finish wall surfaces in period homes with the plasterwork generally attached in two ways – plaster onto hard surfaces, such as brick and stone walls or plaster onto laths, strips of timber nailed to a timber stud frame. Traditionally, the external and loadbearing walls were constructed of solid brick or stone and internal and non-loadbearing walls were constructed using a timber stud frame or ‘studwork’.

Studwork is comprised of ‘plates’ that are fixed on the floor (bottom plate) and ceiling (top plate), ‘studs’ are the vertical supports between the two plates, and ‘noggins’ are horizontal pieces of timber nailed between the studs to increase rigidity.

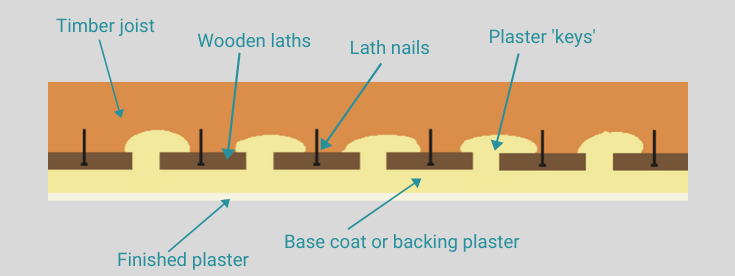

Laths or ‘lathes’ are narrow strips of timber nailed horizontally across the timber stud frame or ceiling joists and then coated in plaster to finish the wall surface. The technique derives from a more basic historical building method called wattle and daub that’s been used for at least 6000 years.

Laths can be sawn or riven (split) with the latter providing greater strength and durability due to the split along the natural grain of the wood. Hardwoods are commonly used such as oak, chestnut and larch.

Wood lath is typically about one inch (2.5 cm) wide by four feet (1.22 meters) long by 1⁄4 inch (6.4 mm) thick. Each horizontal course of lath is spaced about 3⁄8 inch (9.5 mm) away from its neighbouring courses.

The measured spacing is critical and allows plaster to be pushed or squeezed through and behind the laths locking the plaster to the wall as it sets – these ‘curls’ of plaster are known as keys and they play a vital mechanical role in securing the plaster to the wall. Traditionally, lime plaster was mixed with coarse animal hair such as horse or goat hair to reinforce the plasterwork, thereby helping to prevent the keys from breaking away. ‘Haired lime’ also allowed greater flexibility in the lime and helped prevent cracking.

Cut through diagram of a lath and plaster ceiling showing the plaster ‘keys’ that lock the lime plaster firmly in position.

Why did they stop using lath and plaster?

In a word, ‘cost’.

Though there were advantages to the lath and plaster technique – it more easily allowed for ornamental or decorative shapes, provided sound insulation and helped to slow fire spread – new materials superseded lath and plaster because they were simply faster and less expensive to install.

Lath and plaster was a skilled craft and a time-consuming technique and the advent of cheaper, mass produced, pre-manufactured plasterboard meant lath and plaster largely fell out of favour by the 1930s and 1940s. Plasterboard was simply faster and less expensive to install.

But while the technique has slowly died away, it has not been lost forever as there is still a strong demand for lath and plaster in renovation and conservation work. There’s an enormous legacy of buildings with lath and plaster construction across the UK and, as any specialist heritage architect or installer can tell you, lath and plaster is still alive and well today. But why would you choose to use an outdated construction technique that’s been replaced by faster and cheaper methods?

Should I keep lath and plaster walls and ceilings or replace them?

Out with the old and in with the new, right? Well, not quite. There is a lot to consider before jumping in and ripping out your old walls and ceilings and at least three good reasons to keep them in place.

Firstly, if your building is listed then you may need consent from your local planning authority to carry out any significant works to your property and this usually includes the removal of lathe and plaster walls and ceilings. Altering or demolishing a listed building without consent can attract heavy penalties including large fines and even imprisonment. An offence is committed unless works have been specifically authorised by your local planning authority (more on this later).

Secondly, the removal of a lath and plaster wall or ceiling is truly a filthy job and will generate clouds of dirt and old lime dust. It’s not a job for the faint-hearted and it’s not a job that your builder will thank you for. Consider carefully whether it’s really necessary and what you are achieving through its removal. Simple repairs and maintenance can easily be made to lath and plaster walls and ceilings, though you should always consult your local planning authority if your property is listed.

Visit the Real Homes website to learn more about fixing problems with old plaster.

Thirdly, there’s an argument that says that owners of listed buildings are the privileged custodians of our country’s built heritage and that they have a responsibility to ensure that any works they carry out to the building remain faithful to the original. Both plasterboard and gypsum plasters were unknown and unused until well into the 20th century and replacing traditional architectural elements with their modern counterparts would not only alter the character of the building, but could lead to damp and decay by reducing the building’s breathability – its ability to disperse moisture.

Additionally, there are some advantages to traditional lath and plaster construction. Most importantly are its sound-proofing properties and ability to delay and deter the spread of fire.

Lath and plaster, being of hard wood construction and lime plaster, is denser than gypsum plasterboard or drywall and this helps absorb low-frequency sound. Additionally, the irregular shape of the plaster keys between the walls disrupts and deflects noise and cuts down on reverberation and echo. There is an obvious difference between a room fitted with lath and plaster and a room fitted with modern gypsum plasterboard – just ask anyone that lives in a modern plasterboard lined home if they think their building is well sound-proofed.

Traditional lath and plaster is also known to delay and deter the spread of fire. Studies have shown that lath and lime plaster walls and ceilings will spread fire at a slower rate compared to standard gypsum plasterboard. It is known that carbonated lime (lime that has had months to cure) has an inherent fire resistance, but it is also thought that the dense lath and plaster construction reduces the supply of air/oxygen to fuel the fire, thereby reducing its ferocity and delaying its spread.

Can lath and plaster be removed in listing buildings?

The UK is rich in heritage with a wealth of historic and listed buildings across every region. It’s estimated that there are over half a million listed buildings in England alone with many listed for their special architectural interest and importance in their design, decoration or craftsmanship. Special interest may also apply to nationally important examples of particular building types and techniques.

Consent to work on listed buildings can only be provided by local planning authorities and they have a duty to ensure works are carried out in a manner that safeguards the special architectural or historic interest of the building. Consent to work is usually only given once detailed plans for any alterations or extensions are submitted and approved by the local authority – with approval subject to a number of conditions. Commonly these conditions will mandate for the retention of original features and architectural fixtures or surfaces or, where in poor condition, replaced on a ‘like for like’ basis – replacing laths with laths and lime plaster with lime plaster. Establishing a good relationship with your local authority historic buildings officer is vital to running a successful renovation project and it’s advisable to contact them early on if you think Listed Building Consent will be required.

So should I replace Lath and Plaster with plasterboard?

When you compare the two, it is quite clear why modern drywall techniques and plasterboard have superseded lath and plaster construction. It’s simply much faster, more efficient and cheaper to replace lath and plaster with pre-manufactured plasterboard. But cheaper isn’t always better and fast setting, hard plasters and gypsum plasterboard can have a seriously detrimental impact in older buildings by reducing permeability or ‘breathability’ and trapping moisture. This can lead to damp, decay and general deterioration of the building. Before you start ripping old walls and ceilings down it pays to ask yourself what you’re trying to achieve and whether modern materials are right for the property. Most importantly, check whether your property is listed and if you’re in any doubt, seek advice from your local planning authority building conservation officer. Otherwise your quick and efficient renovation project could end up costing you a lot more than you thought.

What about breathable plasterboard? Can I use this instead?

Adaptavate is the first company to develop a breathable plasterboard as a ‘drop in’ alternative to standard gypsum plasterboard. To find out more about Breathaboard, click here.

There are board products on the market that are breathable and can be used in place of standard gypsum plasterboard, but they look and feel very different to plasterboard and are not so easy to work with. The two main options are wood wool board and wood fibre board.

Wood wool board – consists of long-fibre wood shavings bound together into a panel using a cementitious paste. They are a similar size and thickness to plasterboard, but are friable and can be considered tricky to work with. They cannot be scored and snapped like plasterboard and so many smaller sheets are required with a saw needed to cut down to smaller size or shape. Wood wool boards are the ‘go-to’ in the heritage sector for any boarding requirements as they are breathable and excellent carriers for lime plaster. Want to use wood wool boards? Why not use Breathaplasta, our breathable, quick setting lime plaster – follow this link to our product installation guide.

Wood fibre board – consists of wood fibre compressed into thick and rigid boards through the application of heat and pressure and sometimes with additional additives. These strong, durable and dense boards are designed for insulation and can be up to 100mm thick making them ideal for insulation projects, but less well suited to common ‘everyday’ boarding projects and smaller internal spaces.

Want to use wood fibre boards? Why not use Breathaplasta, our breathable, quick setting lime plaster – follow this link to our product installation guide.